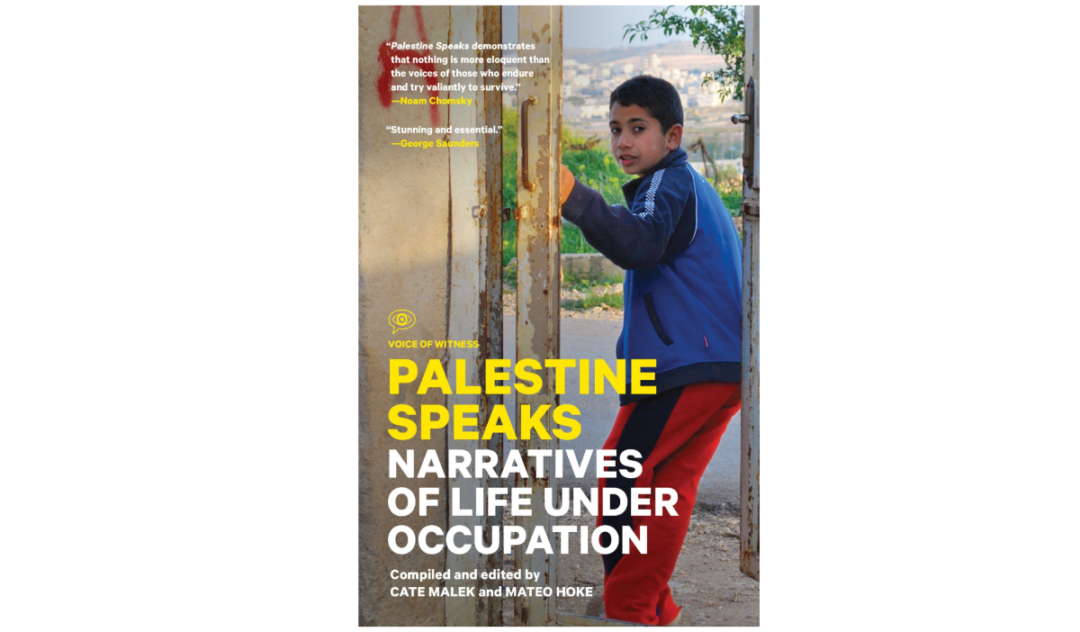

Palestine Speaks: First-Person Narratives of Life Under Occupation

Categorized as: Grantee, Middle East, Our Partners, Stories, Storytelling & Tagged as: Gaza, Palestine, Peace, Voice of Witness on November 29, 2014.

Editor’s note: Voice of Witness (VOW) is a nonprofit dedicated to fostering a more nuanced, empathy-based understanding of contemporary human rights crises. VOW has so far published thirteen titles in its series on a wide variety of social justice issues, ranging from post-9/11 civil rights and the criminal justice system to the experiences of men and women living under oppressive regimes in Burma, Zimbabwe and Colombia. The following story is excerpted from their just-released title, Palestine Speaks: Narratives of Life Under Occupation, edited by Mateo Hoke and Cate Malek. Today we feature a powerful excerpt from Voice of Witness’s new compilation of first person narratives from Palestine.

Jamal’s Story: Ekeing Out a Living as a Fisherman Off the Gaza Strip

JAMAL BAKR, Fisherman, 50. Born in Gaza City, Gaza; Interviewed in Gaza City, Gaza.

VOICE OF WITNESS: During our 2013 trip to Gaza, we meet Jamal Bakr twice at the marina where the fishermen dock their boats. On each occasion Jamal is not fishing; instead, he is watching other boats with expensive nets, and the extensive manpower required to use them, as they bring in their hauls of sardines. Jamal has short-cropped grey hair and a trimmed salt and pepper beard. He has a small frame, and he wears black shoes and slacks even though he spends his days amid the muck of the marina.

Approximately 4,000 Gazan fishermen rely on access to the open waters of the Mediterranean to make a living, but the range in which they can travel by boat has been significantly restricted since Israel imposed a naval blockade on Gaza in 2007. Following the Oslo Accords in 1993, Gazans were permitted to travel up to twenty nautical miles in pursuit of large schools of fish. By the time of the Second Intifada in 2000, that range was reduced to twelve nautical miles, and in 2007, after the imposition of the blockade, the range was further limited to six nautical miles (and sometimes three nautical miles).

In 1999, Gazan fishermen harvested 4,000 tons of fish, and their sale represented 4 percent of the total economy of both Gaza and the West Bank. Today, the fishing economy has collapsed, as Gazan fishermen have depleted schools of sardines and other fish in their limited range. Over 90 percent of Gazan fishermen are living in poverty and dependent on international aid for survival. To pursue fish beyond the permitted range means to risk arrest, the confiscation of fishing boats, or even shooting by the Israeli navy. Some fisherman report being harassed or attacked by the navy even within the permitted fishing zone. According to Oxfam International, an anti-poverty non-profit organization that works in over ninety countries, in 2013 there were 300 reported incidents of border or naval fire against Gazans, and half of those were targeting fisherman at sea.

When we meet, Jamal tells us that he comes from a very long line of fisherman, but that he now relies on international aid to support his family. Since the imposition of the blockade, he can’t rely on catching enough fish to provide meals for his family, let alone catching enough to sell at market. He also shares with us the dangers of the Gazan fishing trade—a profession he has no plans to abandon.

Jamal Bakr, Fisherman. Photo by Mateo Hoke.

Jamal Bakr, Fisherman. Photo by Mateo Hoke.

My Children Are the Most Important People in My Life

JAMAL: I was born here in Gaza in May 1964, and I’ve always lived off of the sea and what it provides. My family takes its job from our ancestors—we’ve been fishermen since long, long ago. I first went out on a fishing boat with a brother-in-law when I was twelve. I loved it immediately and knew that was what I wanted to do with my life. My father taught me to fish when I was thirteen. I got my own boat when I was sixteen, and I fixed it up until it was in good enough shape to sail in the sea. I’ve fished now for thirty-five years. I’ve never done anything else.

I’m very close to the other fishermen. I’ve worked alongside them for decades, and we see each other more than we see our own families!

But my children are the most important people in my life. It used to be that my parents were most important, and now it’s my children. I’ve been married to my wife Waseela for twenty-eight years—we are cousins, and our parents arranged for us to be married. I have eight daughters and one son. We fishermen love to make more and more children because we want sons to help us on the boats. I think of having more children, God knows, but I have to convince my wife! My son Khadeer is eighteen, and he’s a fisherman already. He left school after the sixth grade because he wanted to work with me. He’s been a full-time fisherman ever since, but he’s not old enough yet to be very reliable. I love my daughters, but it’s against tradition for women to be fishermen.

Before the blockade, my family used to go far out into the sea and get amazing amounts of fish.(1) We’d find mostly sardines, but also plenty of mackerel. I could make $500 in a single day sometimes. Fishing around Gaza City was actually better when Gaza was still occupied, since we had more freedom to travel throughout the sea then.(2) But things have been especially difficult with the blockade. Actually, things have been especially bad ever since Gilad Shalit was captured.3 Before his capture, we used to have access to twelve nautical miles around Gaza City for our fishing boats. But since then, the restrictions have been much tighter. It might change a little, but whether it’s three miles or six miles doesn’t make much of a difference. We can’t find much in those waters—only a few sardines. There are no rocks for bigger schools of fish to live around, since it’s mostly only mud in the zone where we’re permitted to fish.

When we go out on the sea, we’re often in crews of at least three or four. Our boats may be about twenty feet long, with roofs and a closed compartment in the center that we fill with ice and use as a cooler for our catch. We have lights mounted to the roofs of our boats to spot schools of fish in the early morning and late evening, and we use GPS devices so we can return to the best available spots and also make sure we’re not crossing the boundaries of the blockade. When we find fish, we have nets we use to bring them in. But these days, it’s not so easy to find fish.

Since the blockade, most months I don’t make a single penny. It’s not only that I don’t make money, I even owe the gas station money because it costs a lot to fuel up the boat. Then I don’t make anything, so I can’t pay. So at the end of the day, most days, I’m losing money. When I do catch fish, I take them to the market behind the marina. But most days there’s nothing to sell, so I just sit at the marina with other fishermen. The Gaza seaport—the marina—is pretty much a mile-long strip of concrete where fishermen tie up their boats. There’s a gate separating the marina from the rest of the city’s shoreline, but not much else there besides a strip of concrete. Recently, a Qatari–Turkish-funded project added some tables and chairs where families can congregate on Thursdays and Fridays. When we get together at the marina, we mostly talk about the fish we found or didn’t find out at sea.

But even when there’s not enough fish to sell in the market, I feed my family sometimes with the fish I can catch. We eat a lot of sardines when I can catch them. Mostly for dinner, but sometimes for lunch as well if we’ve caught enough. We’ll grill them or fry them, and always eat them with rice. The best kind of fish I catch is the denees.(4) That is a delicious fish.

Every Single Day, I Expect To Be Killed

When I’m out on the water, I’m nervous about being shot. Shootings happen all the time on the water. I have a cousin who got killed a year ago, when he was just going out on the water for fun. He was nineteen, and he’d just gotten engaged. He went out on a Friday with his uncle, and, at the time, the fishing zone was limited to three nautical miles. They might have gone too far out. My cousin didn’t do anything wrong, he was just a little out of the restricted area. There was no good reason why he was shot. I probably see around three Israeli gunboats every day I go out.

Usually, they are off in the distance, but sometimes they get quite close. They are about forty feet long, with a crew of twelve or so. Sometimes they’ll pull close to a Gazan fishing boat like mine and simply shout curses through a megaphone. When this happens to me, I just pretend like they aren’t there. They couldn’t hear me if I tried to say anything back, anyway. They have water cannons that they sometimes fire on boats, as well as rockets and machine guns.

Every single day, I hear that someone got shot at. Every single day, I expect to be killed. Whenever I leave my home in the morning, I’m not sure I will get home alive. That is what it’s like to be a fisherman in Gaza. I don’t know how to keep myself safe, because we don’t have time to think of how to protect ourselves when the shooting starts. When the navy starts shooting, a fisherman doesn’t even have enough time to put on a life jacket.

The soldiers often shoot for no reason at all. It doesn’t have to be because someone went out of the restricted area, like my cousin. It could be because of something else that was happening in Palestine, or the mood of a soldier. Sometimes, if the soldier’s girlfriend broke up with him, he comes and—just because he’s angry—he shoots up the fisherman.

They keep you guessing. I don’t think soldiers who shoot always have a reason, really; they can just do whatever they want without fearing anyone.

In the middle of November 2012, I didn’t work at all during the week of bombing.(5) After the cease-fire later in November, I started going out again, and so did my son Khadeer. As part of the cease-fire, we fishermen were supposed to be able to go out up to six miles, so we were all eager to see what we would be able to find in the waters we could now get to.

At that time I had two boats—my old boat that I got at sixteen, and a newer, nicer one with a new motor that I had saved up to buy. Three days after we started fishing again, on November 28, Khadeer went out early in the morning to fish with three of his cousins. They took my new boat out on the water. Later that morning, his cousins showed up at my house. When I saw them, I thought right away that my son had been killed.

My nephews told me that they were fishing out in the sea, about two miles from the marina. There were maybe twenty other boats around fishing in the same area. Suddenly an Israeli gunboat appeared a few hundred feet away. Without warning, the boat fired a missile at my boat’s engine and completely disabled it. It caught fire. Nobody was injured, they just destroyed the engine. That was their introduction. Then an Israeli navy guy called to Khadeer and his cousins through a megaphone and told them to strip to their underwear and to jump into the sea, because they were going to blow up the boat. My son jumped in the water, and they hit the boat with another missile and it exploded. After the boat was destroyed, the navy guys began shooting in the water all around where my son and his cousins were swimming. They were all really scared. Then the Israeli boat pulled up and grabbed Khadeer out of the sea. His cousins watched him get handcuffed to the mast of the boat. He was in his underwear, and it was one of the coldest days of the year and very windy on the sea. Khadeer’s cousins then swam to another fishing boat, got a lift back to shore, and came to see me.

That morning, I stayed home waiting for news of my son. I thought the police might call with news that he’d been arrested by the Israelis. At some point that morning, friends called to tell me that they’d talked to fishermen who had stayed for a while near the attack on my son. They said he was still okay, that he was aboard the Israeli boat. But I wasn’t even focusing on what my friends were saying, because my heart was about to stop.

Then, a few hours later, around three in the afternoon, Khadeer came back. When I saw him, I felt that I got my soul back. The first thing he said was, “We lost the boat.” I told him, “You shouldn’t have to worry about the money and the boat. It’s fine. As long as I didn’t lose you.” It became a big huge gathering of friends and family, and everyone was crying.

Later, Khadeer told me that he was handcuffed to the mast of the Israeli gunboat for three hours. Then soldiers refused to take him to shore, because they didn’t want their bosses to know what they’d done to him. They didn’t have a reason or excuse for it. While he was handcuffed, they fired on another boat. Eventually, they threw him in the sea and told him to get the nearest fishing boat to take him back to shore. Imagine if some- thing bad happened to him—how could you throw him again into the sea without checking to see if he was close to freezing to death? I think if something bad had happened to him, none of them would have ever cared. Maybe they would have said, “It was by mistake.”

I felt really lucky because when I lost the $10,000—the value of the boat—I felt like I’d lost money, but then I got compensated with millions of dollars by getting my son back. I told Khadeer, “Don’t think of it. Don’t worry about it. This just happens.” I didn’t want to let him feel too scared by the experience. He started fishing again after one week. By now, my family is used to the nature of this work. When we go to the sea, they know—my son and I are either going to be back home in the evening or we’ll be killed. So we all live with this fact.

I feel really disappointed because my life is always in danger, and it’s not even for any good reason. It’s not for a good thing at the end of the day. Before the blockade, I used to face many hardships, but it was for something good, because I used to make a good income. But now I’m sacrificing my life for nothing. Now I have a dead heart. I don’t care about shooting, or anything that comes to me. If anyone starts to feel a bit weepy about their lives, they shouldn’t go out on the water.

The important thing is that I have Khadeer back, but the attack has totally affected my life, because the boat that we lost was the new one, and it had a good motor. Now I have only the older boat. Now I’m using my friend’s motor because I don’t have enough funds for my own.

Even this old boat is at risk. Another worry that fisherman have is boat seizures. The Israelis find all sorts of reasons to seize boats. Then they’ll tell the fisherman that his boat will be returned, and it never is. Sometimes I think that Israel is financially fighting Palestinians in Gaza. Because they seize boats for reasons that have nothing to do with security issues, reasons that have more to do with fighting people and their source of income. Sometimes I think if they see a fisherman trying to haul in a huge amount of fish, they keep shooting until he leaves everything behind and runs. So the main target is to control what financial benefits people can get out of the sea.

It’s really hard now to support my family through fishing. It’s really bad. Before, I used to donate money to charity. But now I’m living on international aid. It’s only because of this that I can survive. We get some support from CHF, but it’s not money. It’s just flour and oil.(6) I could make $500 a day before, and now I haven’t made anything for a month. If I could make even $30 in a day, that would be an incredible day of fishing. But I never feel discouraged. I’m always hoping for the best.

I owe a lot of money to a lot of people. I’ve borrowed from family and friends. People don’t hassle me about it yet, but I feel the pressure whenever I see them. Since the incident of the boat, I don’t sleep much, only two hours a day. I didn’t sleep at all last night. How would I sleep knowing everyone wants money from me? And, more than this, I wake up in the morning and I’m not sure I’ll be able to feed my children. So it’s becoming complicated, and it’s affecting me and my state of mind because I’m not feeling fine. Still, I never thought of getting any other job because I feel like I’m a fish. If I leave the sea, then I will die.

Footnotes:

(1) Israel’s blockade of the Gazan ports began in 2007, partly in response to Hamas taking power in the Gaza Strip. Egypt also formally restricted its borders with Gaza at the time. For more information, see Appendix I, page 295.

(2) Gaza was fully administered by Israel from the end of the 1967 war until the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993. Israeli settlers and the Israeli military continued to occupy parts of Gaza until September 2005, when Israel evacuated all settlers from the strip and withdrew military forces. For more information, see Appendix I, page 295.

(3) Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit was captured in 2006. He was released as part of a prisoner exchange in 2011. For more information, see Appendix I, page 295.

(4) Denees is the gilt-headed bream, often called dorade in U.S. markets.

(5) Israel targeted Gaza with bombings during eight days starting on November 14, 2012, during what it termed Operation Pillar of Defense. For more information, see Appendix I, page 295.

(6) Cooperative Housing Foundation (CHF) is an international aid non-profit now known as Global Communities. Following the air strikes of 2012, Global Communities began distributing food to 47,500 Gazans in partnership with the United Nations.

Consider donating to Voice of Witness’ year-end “Fund It Forward” campaign so that these kinds of stories can be shared with as many people as possible. Find out more information here.

LEARN more about Voice of Witness’s approach to storytelling here.

SHARE this story with your networks; see menus at top of page and below this list.

DONATE directly to Voice of Witness’s mission of illuminating human rights crises through oral history, here.

SUBSCRIBE! Like what you see? Click here to subscribe to Seeds of Hope!